The murder of George Floyd and the subsequent mass of wrath that followed brought back to memory a few excerpts from a book I read in college. These are the words of American Theologian, James Cone, from his book, “The Cross and the Lynching Tree”. Written nearly a decade ago, they need no preface.

The crucifixion of Jesus by the Romans in Jerusalem and the lynching of blacks by whites in the United States are so amazingly similar that one wonders what blocks the American Christian imagination from seeing the connection.

To reflect on this failure [to connect the analogy of the cross and the lynching tree] is to address a defect in the conscience of white Christians and to suggest why African Americans have needed to trust and cultivate their own theological imagination.

The cross has been transformed into a harmless, non-offensive ornament that Christians wear around their necks. Rather than reminding us of the ‘cost of discipleship,’ it has become a form of ‘cheap grace,’ an easy way to salvation that doesn’t force us to confront the power of Christ’s message and mission. Until we can see the cross and the lynching tree together, until we can identify Christ with a ‘recrucified’ black body hanging from a lynching tree, there can be no genuine understanding of Christian identity in America, and no deliverance from the brutal legacy of slavery and white supremacy.

In the 7 years that have passed since I read these words, neither I nor the world has budged when a Black American died. After Trayvon Martin was shot, I forgot. After Philandro Castile died, I forgot. After Deondre Hamilton was killed, I forgot. After Eric Garner suffocated, I forgot. For 7 years I watched as Black Americans were hung on a tree. And I forgot.

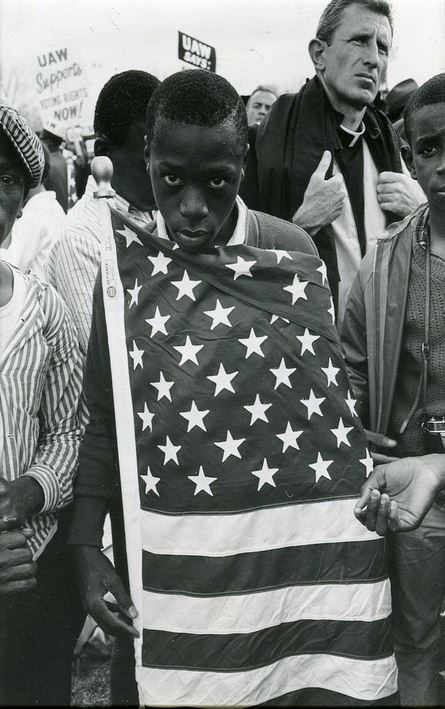

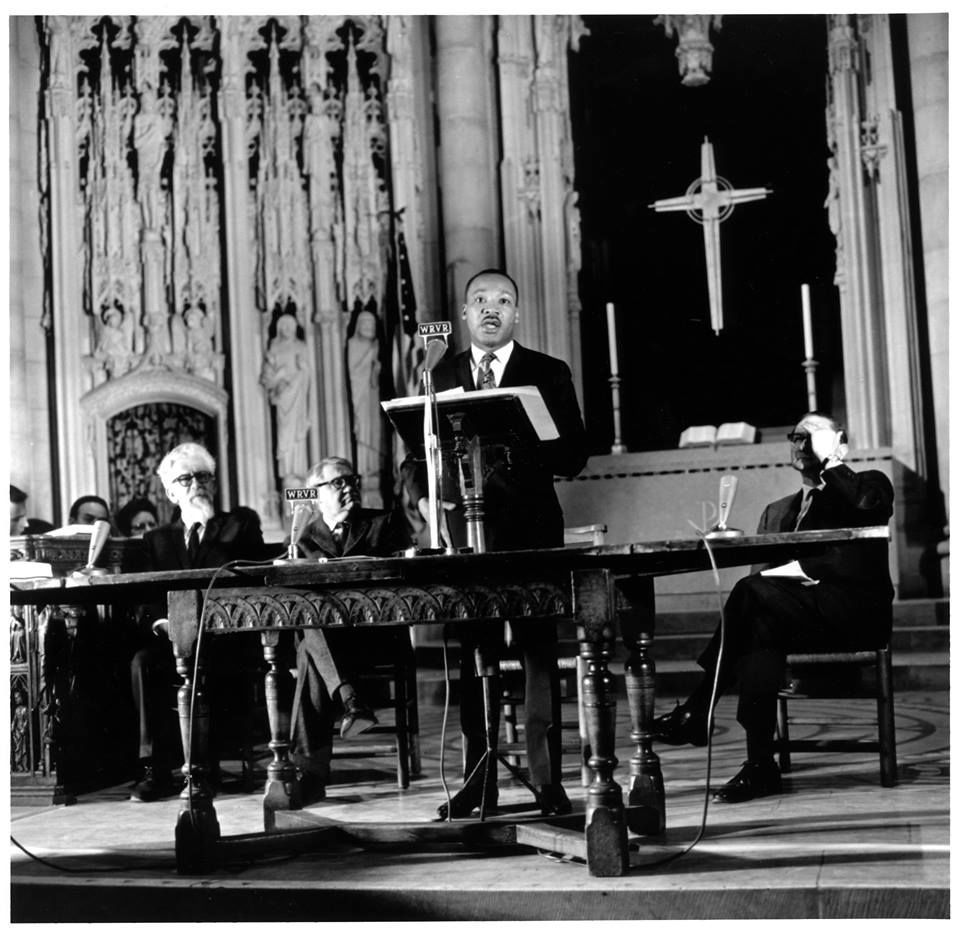

It is America’s eternally unresolved query: what will Lady Liberty do with her black citizens? James Cone’s critique of American Theology is a war hammer that bludgeons beyond the boundaries of theology; it critiques American identity. America is a young nation with an unresolved problem that has been hidden beneath the guise of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. To understand what it means to be American, an individual has to ask how they have resolved the enslavement of Black Americans.

When the riots started I was upset. At one end of the spectrum, I understand that a riot is the language of the oppressed. But at the other end of that spectrum, I also don’t think violence or threats of violence are a solution. In a body as freeform and seemingly anucleate as Black Lives Matter (in addition to the larger unorganized visceral response), we cannot realistically expect a uniform reaction to the murder of George Floyd. There are many cries and wails today, and we should look closely to separate the anguish from the ruckus.

In a play there are many parts. In the pit are the strings. At front and center is the prima donna. In the wing are the supporting thespians. Above the curtains are the stagehands. All contribute to the play. Similarly, in a movement like Black Lives Matter (and certainly in our individual responses to such a movement), we all contribute to that play. And we are all at different stages.

When my friends blacked out on Instagram, I couldn’t find it in me to do it too. When my friends went out and marched, I didn’t think I had it in me either. I take a lot of time to process things, and, at the core of the processing, is a desire to be authentic.

Everyone has their own voice and response. No one should be shamed for reflecting on these days. “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.” If you are still processing, you are not doing “nothing”. Your thoughts will inform your voice, and you will discover an authentic way to respond.

But this moment is not about us. It’s not about me. It’s about Black America.

Look at the history of this nation. It is 200 some odd years old and the scars of slavery have yet to scab over. What we see today is the cumulative cry of 200 some odd years of anguish. 200 years! If my mother yells at me, I’m quick to respond; but if a black man dies, I just forget. That’s my privilege. That’s something that Black Americans do not have.

This moment is for Black Americans, for Black America. My voice has no place in this–at least, not at the forefront. After George Floyd, it is incumbent upon us to listen.

As the nation reflects on this impasse, we should acknowledge that we are entering a complicated sphere. There already exists an incredible amount of literature and discourse regarding liberation, justice, equality, etc. The dialogue and rhetoric is established. Part of the resolution to America’s eternal query is education. Listen to experts and to people that have thought on this. Our 15 minute opinion is exactly that. Their years of reflection–and experience living in what we are discussing–are exactly that. There is something to learn here because, clearly, we haven’t learned much in the past 200 years. If we can’t see it when it’s shown–or at least understand the tiniest fraction of what Black America is pointing out–then our vision requires revision. “Why do you look at the speck of sawdust in your brother’s eye and pay no attention to the plank in your own eye?”

This moment is the perfect storm. If it weren’t for quarantine, would we have had this large of a response to George Floyd? If it weren’t for our President, would we have had such a dichotomous diatribe? If it weren’t for the death–perhaps sacrifice, even–of yet another Black American, would we even be at this moment?

2020, despite all of its luster and gleam, is the opportunity to move our nation “to higher heights of democracy and the great dream of justice and humanity”. We have to listen to this penultimate of 200 years lest we simply, yet again, forget.

This post is a sort of stream of consciousness regarding the current events. I am not writing to inject my own voice into the discourse. Rather, I hope that I can be a voice for other processors and introverts like me. My mind is already dreaming up ways to be involved, to be an ally, and to finally *listen* to and *act* for and with Black America.